Rebalancing

Tools to rebalance your portfolio.

Portfolio rebalancing

Portfolio rebalancing is a fundamental practice in portfolio management to maintain the desired risk/return profile over time. Even the most experienced investors see their portfolio evolve unpredictably: asset classes with better returns end up weighing more, while those in decline become smaller. Without intervention, a portfolio can become unbalanced, exposing the investor to unintended risks. Rebalancing means realigning allocations to initial objectives, partially selling excess assets and purchasing insufficient ones.

Example: Imagine an initial portfolio of 60% stocks / 40% bonds. After a year of strong stock upside, you could find yourself with a 70% stock/30% bond situation. This implies a greater risk than expected. The rebalancing would bring the composition back to 60/40, selling part of the stocks (overweight) and buying bonds (underweight). This brings your portfolio back into line with your original risk tolerance.

In this section we explore rebalancing under three key dimensions: strategic, operational and behavioral. Each offers different insights into when and how to rebalance and how to maintain the necessary discipline.

Strategic dimension: approaches to rebalancing

From a strategic point of view, there are various approaches to deciding when to intervene on the portfolio. Popular strategies include fixed-interval approaches, threshold-based approaches, and hybrid or cost-oriented methods. The choice depends on your investment style, the time you can dedicate to management and your attention to costs.

Periodic rebalancing (calendar-based)

It consists of checking and rebalancing the portfolio at regular pre-established deadlines (for example annually, semi-annually or quarterly). This method is simple and disciplined: at each interval the allocations are brought back to target levels regardless of what has happened in the meantime.

Advantages:

- Promotes discipline by eliminating frequent decisions.

- Avoid having to constantly monitor your portfolio.

- Scheduling the rebalancing (e.g. every December 31st) helps to include it in your financial calendar.

- It often limits operations (1-2 times a year) thus containing costs in the long term.

- It is suitable for long-term portfolios where continuous reactivity is not needed.

Disadvantages: it could rebalance when it is not needed (minimal deviations) or, on the contrary, wait too long after strong market movements. In practice, an annual rebalancing might miss large deviations that occurred mid-year, or rebalance when the portfolio is still within acceptable tolerances. Despite this, for many investors an annual or semi-annual check is a good compromise between inertia and hyperactivity.

Threshold-based rebalancing

In this approach there are no fixed dates, but tolerance thresholds are defined beyond which rebalancing is triggered. For example, you could establish that each asset class must remain within 5% of its target weight: if the equity rises from 60% to 66% (above 63%), then we proceed to rebalance.

Advantages:

- It ensures that the portfolio never strays too far from the desired asset allocation.

- It helps to sell what has gone up a lot and buy what has gone down a lot (rule “buy low, sell high”).

- Avoid unnecessary operations when variations are minimal.

Disadvantages:

- Requires frequent monitoring, especially in volatile markets.

- It can lead to more frequent operations with higher costs.

- Choosing the right threshold is not trivial: too narrow = too many rebalancing; too wide = risk of excessive imbalance.

Practical example: with a threshold of 5% on a 60/40 portfolio, action is taken only if the equity component falls below 55% or rises above 65%. If the movements remain within this “corridor of tolerance”, you let them go.

Cost-aware and hybrid approach

Many advanced investors adopt hybrid strategies, which combine the two logics above, also taking into account rebalancing costs. A common approach is: periodic checking (once a year) but rebalancing only if deviations exceed a certain threshold.

In practice:

- Fixed frequency checks: the portfolio is examined at regular intervals.

- Application of thresholds: action is taken only if some weight goes outside the band.

- Cost-awareness: the impact of costs and taxes is assessed before operating.

This approach allows rebalancing only when the benefit clearly outweighs the transaction costs and any tax impact. Small or high-fee portfolios tend to benefit from wider thresholds or lower frequencies, while larger portfolios can afford more frequent adjustments.

Other strategic approaches

In professional contexts, variations such as:

- Bands differentiated by asset class: different thresholds based on the volatility of each asset.

- Opportunistic rebalancing: extra-calendar interventions in the event of extraordinary market events.

- Intentional failure to rebalance: conscious choice not to rebalance to maximize return, accepting greater volatility and drawdown (extreme approach, not suitable for most investors).

In summary, the strategic dimension of rebalancing concerns devising a plan: establishing when and based on what to rebalance. There is no single solution valid for everyone: the important thing is to have a clear strategy and follow it consistently.

Operational dimension: frequency, costs and tools

Once the strategy has been defined, it is necessary to deal with the operational aspects: how often to carry out rebalancing, which costs to consider and which tools to use.

Rebalancing frequency and timing

The frequency depends on the approach chosen. Some operational guidelines:

- With a fixed periodic approach, the typical recommended frequency is annual or semi-annual.

- With threshold approaches, the frequency depends on market movements: in stable markets you may not rebalance for years, in turbulent phases you may intervene more often.

- A mixed approach involves regular checks (e.g. quarterly) but operations only in case of overruns.

Avoiding extremes is crucial: never rebalancing can lead to an out-of-control portfolio; rebalancing too often generates unnecessary costs and risks turning into market timing.

Transaction costs and tax considerations

Rebalancing involves costs that, in the long term, can erode performance:

- Trading commissions: Every sale and purchase has a cost.

- Bid-ask spread and slippage: implicit costs that increase with illiquid instruments.

- Tax implications: Realized capital gains may be taxed, reducing the invested capital.

- Opportunity costs: Selling a strongly trending asset can reduce potential future returns.

To manage costs, you can:

- Limit attendance and turnover.

- Exploit cash flows (contribution rebalancing), directing new payments towards underweight assets or withdrawing from overweight ones.

- Use tax-efficient tools, when available, and select low-cost brokers.

Active rebalancing (selling and buying) is immediate and precise, but involves certain costs and potential taxation. Passive rebalancing via cash flows is less expensive but slower and dependent on available liquidity.

Portfolio tools and monitoring

To rebalance you need to know precisely where the portfolio is compared to the targets:

- Current allocation calculation: Percentage weights by asset or asset class.

- Deviation metrics: deviation in percentage and absolute value compared to the target.

- Risk Delta: Check whether volatility and overall risk are moving away from the expected profile.

Useful tools:

- portfolio management platforms or well-structured spreadsheets;

- alerts and notifications for critical thresholds;

- automatic rebalancing functions offered by some brokers or robo-advisors.

Documenting operations (date, amounts, reasons) helps evaluate the effectiveness of the process over time and maintain discipline.

Behavioral dimension: management of biases and investment discipline

Rebalancing is also a psychological challenge: it often means going against instinct. Selling what goes up and buying what goes down is counterintuitive, but it is part of the anti-panic logic of rebalancing.

The main behavioral obstacles are:

- Greed and recency bias: Refrain from selling winning assets.

- Loss aversion: Avoid buying falling assets.

- Inertia: Procrastinating rebalancing.

- Overconfidence: believing that one’s portfolio must “derive” from targets because “times have changed”.

- FOMO and gregarious behavior: Follow the market instead of the plan.

To maintain discipline:

- Write a plan with clear rebalancing rules.

- Recognize bias and observe your emotions before acting.

- Automate or delegate where possible.

- Keep the long term perspective and remember the reason for the initial asset allocation.

A well-rebalanced portfolio does not eliminate downsides, but reduces the extremes, making the investor’s experience more manageable and increasing the likelihood of remaining consistent with the plan.

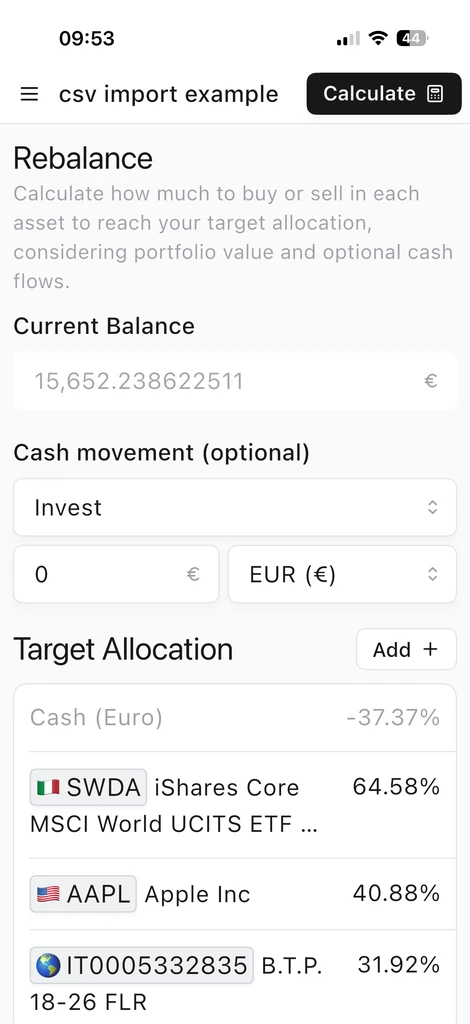

Rebalancing on Wallible

On Wallible you have the opportunity to calculate the purchase/sale transactions to be carried out for each security in the portfolio based on the desired asset allocation. This allows you to quickly move from analysis to practice, with clear guidance on how to realign your monitored portfolios.

Furthermore, you can simulate your investment strategies and choose the rebalancing period directly in the Portfolio Simulator, so as to evaluate the impact of different frequencies before applying them in reality.

Conclusions

Portfolio rebalancing, in its strategic, operational and behavioural dimensions, is an essential pillar of good financial management. It allows you to keep your allocation in line with your objectives and risk tolerance, optimizing costs and discipline.

In conclusion, a rebalancing well done:

- Keeps portfolio consistent with initial plan.

- Harness biases and strengthen decision-making discipline.

- Consider costs and benefits, avoiding unnecessary expenses.

- Adapts to the investor’s situation, with clear and consistently applied rules.

Rebalancing is a common sense financial practice: it may seem counterintuitive, but it helps well-constructed portfolios stay that way over time. The success of long-term investing depends not only on which assets you choose, but also on how you manage them along the way.